Published in Promoting A Culture of Peace, Kuala Lumpur: Cahayasuara Communications Centre for Signis Asia, 2005, pp. 42-8.

MAINSTREAMING THE MINORITIES: THE CASE OF THE MANDAILINGS IN MALAYSIA AND INDONESIA

By Abdur-Razzaq Lubis

Malaysian Representative, Mandailing All-Clans Assembly (HIKMA)

The issue of our time, the survival of human beings with individuated consciousness and communal ties, is in peril… Freedom, then, is the path to his new life. A freedom which begins with the individual, confirms him in his place with his people [ethnicity] and his language and his culture, yet by that specific location of his being there, grants him a world perspective to recognize his brothers and sisters elsewhere in their ‘different ness’ and their challenge. (The World Crisis)

Who are the Mandailings?

Our homeland is called tano rura Mandailing [the land and water of Mandailing], on the south-western corner of the island of Sumatra. Today it is known as the kabupaten of Mandailing-Natal, or the regency of Madina. The Mandailings are Muslims as well as Christians. For centuries the Mandailings have migrated throughout the peninsula and Indonesian archipelago.

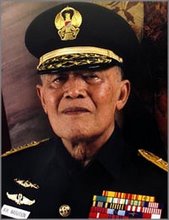

The Mandailing’s most significant contribution to regional peace was to help end the Malaysian-Indonesian Confrontation. The ‘Konfrontasi’ arose as a result of Sukarno’s opposition to the formation of Malaysia, which the Indonesian’s saw as a British-inspired polity. Two Mandailings - Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Adam Malik and General Haris Nasution conspired to broker peace between the two neighbouring countries. At the time of Konfrontasi, Haris was a general in the Indonesian army and his nephew was the chief of staff in the Malaysian navy.[1] General Haris Nasution had flatly refused to go to war with Malaysia as he likened it as fighting his own kinsmen.

Indeed, Adam Malik felt that his main task as Indonesia’s Foreign Minister was to end the Confrontation. He even challenged Sukarno over the matter. He achieved his objective when the two neighbouring countries agreed to end the Confrontation. After the peace treaty was signed in 1966, the first thing Adam Malik did was to make a trip to Malaysia and visited Chemor (his mother’s birth place) in Perak, to reassure his relatives.[2]

In spite of their of their enormous contributions to politics, society, music, literature and the press both in Indonesia and Malaysia, Mandailings continue to be culturally marginalized in Indonesia and Malaysia. Academic works have subsumed them under the categories of the Angkola, Batak and Malay. In Malaysia, racial politics and state-sponsored socio-economic engineering in the name of nation building, backed by the academia, have resulted in the acculturation of the Mandailings into the dominant Malay racial category. In Indonesia, the Mandailings have been lumped into the dominant Batak group since the Dutch colonial era. As a result, the basic human right of the Mandailing to define themselves has been overlooked by most Malaysian and Indonesian intellectuals who have accepted the state’s discourse on ethnicity. Indeed,

In the animal kingdom, the rule is, eat or be eaten, in the human kingdom, define or be defined. (Thomas Szasz)

Are the Mandailings a minority in Malaysia?

What is a minority? Who defines a minority? Who are the beneficiaries of minority rights?

Thus far there are no definite answers. The difficulty in arriving at an acceptable definition of the term ‘minority’ lies in the variety of situations in which minorities exist. Some live together in well-defined areas, separated from the dominant population, while others are scattered throughout the national community. Some minorities has a strong sense of collective identity based on a well-remembered or recorded history; others retain only a fragmented notion of their common heritage. In certain cases, minorities enjoy – or have known – a considerable degree of autonomy. In others, there is no past history of autonomy or self-government. Some minority groups may require greater protection than others, because they are threatened by ethnic or cultural cleansing or facing extermination (genocide).

Despite the difficulty in arriving at a universally acceptable definition, various characteristics of minorities have been identified, which, taken together, cover most minority situations. The most commonly used description of a minority in a given State can be summed up as ‘a non-dominant group of individuals who share certain national, ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics which are different from those of the majority population’. It has been argued that the use of self-definition which has been identified as ‘a will on the part of the members of the groups in question to preserve their own characteristics’ and to be accepted as part of that group by the other members, combined with certain specific objective requirements, could provide a viable option.

As far as statistics go, the Mandailings are in the majority in their homeland, but they are a minority in Indonesia and Malaysia. According to the 2003 census, the population of the regency of Madina stands at 369,691 the majority of which are Mandailing.[3] In 1982, the Mandailing Welfare Association of Malaysia (IMAN) estimated that there were about 30,000 Angkolan and Mandailings in Malaysia.[4] The Angkolan are the neighbours of the Mandailings to the north of the homeland. Many people of Angkolan descent in Malaysia, consider themselves Mandailings. Assuming that the 1982 figures are correct, the author estimates that there are about 50,000 people of Mandailing and Angkolan descent in Malaysia, today.

In Indonesia, the Mandailing ethnic category does not exist as the Indonesian state wants Indonesians to see themselves as bangsa Indonesia. In Malaysia, the DAP’s Malaysian Malaysia, and the government’s bangsa Malaysia is no different. It is expedient for a political party like the DAP or the government to call for a national identity as the DAP dominated by the majority Chinese ethnic group and the government dominated by ethnic Malays, would have their identity secured in the bargain.

Mandailing Dilemma

Suffering from acute identity crises, Mandailings use passing off when convenient. Upwardly mobile ‘passing’ can have its uses; during the period of Indonesian resurgence under Sukarno it was popular to be a Sumatran, but during Confrontation it was safer to be a Malaysian. Since then the Malaysian government has tempted people of Indonesian descent to identify themselves as bumiputra, sons of the soil/land, the natural inheritors of the Malay tradition and rights. In modern Malaysia, passing off as Malays for government contracts, joining the Malay dominated civil service, to enter politics; essentially to climb the social ladder. Mandailing also use regional identities to obscure their descent.

History and nation-building processes has seen to it that the Mandailings people are divided into two ethnic and cultural identities; in Indonesia they are Batak-Mandailing and in Malaysia as Malay-Mandailings. On one hand they are under the hegemony (ketuanan) of the predominantly Batak Christians and on the other, they are under the hegemony of the Malay Muslims. Torn between two religious and ethnic identities, the Mandailings are caught in a dilemma between two equally undesirable alternatives. Both want to appropriate the Mandailing’s differentness.

The pressure to conform to either Batak or Malay identity is both religious and cultural; the difference is that in Indonesia the weight of the state is not behind it. In Malaysia, conformity is compelled by legal means as well as with the might of the state through national policies such as cultural policy and grant concession development. In Indonesia, regional and ethnic identities is experiencing a surge in the euphoria of regional autonomy and devolution of power; in Malaysia the debate that the Mandailings are a sub-group of the Malay stock/race is considered close at the highest level and the thing to do is conform, and not rock the boat.

Although the definition of race remained uncertain, the term itself has stuck in administrative and academic language of today. In vogue is the idea of ‘Melayu inklusif’ (inclusive Malay), based on the colonial perception that the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago and the peninsula are all of the Malay race/stock (rumpun Melayu).[5] The Malay nationalists driven by fears of the ‘yellow peril’ are not letting up in its designs to incorporate the diverse ethnic groups in insular Southeast Asia into the Malay agenda in opposition and to check the so-called Nanyang Agenda of the Overseas Chinese.

Peaceful Coexistence

Because of the legacy of colonial rule in Malaysia, the most important political parties are racial representing the interest of individual ethnic groups. I would describe the brand of majority politics in Malaysia as racial rather than communal. Even though the ethnic interest of the racial trinity of Malays, Chinese and Indians, have been largely attended to, the racial threat remained; Malaysia is also divided along linguistic, religious and social lines. Since independence the principal pre-occupation of the government have been the preservation of the country’s fragile unity and the welding of a truly united nation, of which the survival or eventual demise of the new nation, depends on.

Opposition to the special privileges of one dominant race appeals to the members of minority groups who feel that their own interests are thwarted by the current Sino-Malay-Indian system, which leaves smaller groups in an isolated and exposed position. Communal politics as it serves to benefit a community is in itself not a bad thing altogether, but racial politics by its nature excludes and discriminates. Barisan Nasional (BN) or Barisan Alternatif (BA) pander to, and knowingly or unknowingly serves this brand of politics as their constituents are mainly from the three dominant ethnic groups.

That diversity characterizes the great majority of countries in the world, and that with the end of the cold war and bipolar international order, claims to ethnic, religious, cultural and religious varieties are becoming stronger. The ‘rediscovery’ of ethnicity and cultural identities has created an awareness of the need to cope with the management of ethnic and cultural diversity through policies which promote ethnic and cultural minorities participation in, and having access to the resources of society, while maintaining the unity of the country. The fears that cultural diversity, or multiculturalism, has the potential to foster highly divisive social conflicts owing to the highly contentious thesis by Huntington’s on the clash of civilization in which religion is argued to play a crucial role; it can be argued that the state and social policies can check and intervene and reduce the potential for conflict. Multiculturalism, as a systematic and comprehensive response to cultural, ethnic and religious diversity, with educational, linguistic, economic, social and religious components and specific institutional mechanisms, has been adopted by a few countries, notably Australia (not necessarily a good example), Canada and Sweden.

Special rights for minorities are not privileges but basic civil rights to make it possible for minorities to preserve their identity, characteristics and traditions. Special rights are just as important in achieving equality of treatment as non-discrimination. Only when minorities are able to use their own languages, practise their own religion, culture, etc., benefit directly from state services, as well as participate fully in the political and economic life of the state, can they begin to achieve the status which majorities take for granted. Affirmative action in the treatment of such groups, or individuals belonging to them, is justified if it is exercised to promote effective equality and the welfare of the community as a whole. This form of equitable system may have to be sustained over a prolonged period in order to enable minority groups to benefit from society on an equal footing with the majority. Recognition and entitlements would secure their cultural survival, guarantee peaceful co-existence with fellow humankinds and their well-beings in a world where cultural and human diversity matters. To sum up,

…The promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities contribute to the political and social stability of States in which they live.

(Preamble of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities)[6]

I would add that the promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to a minority group contributes to multiculturalism, both to cultural and human diversity, as human diversity is equally at stake today as bio-diversity, threatened by the same forces threatening bio-diversity, that is, globalized homogenized culture, Machiavellian development and malicious capital. We dream of a world where we can afford to sip a cuppa of the famous ‘Mandheling Coffee’ on equal terms.

[1] A.H. Nasution, Memenuhi Panggilan Tugas, Jilid 1: Kenangan Masa Muda, Jakarta: Gunung Aung, MCMLXXXII: 6.

[2] Adam Malik, Mengabdi Republik, Jilid 1 Adam Malik Dari Andalas, Gunung Agung, Jakarta, 1978; Abdul Rahman Rahim, Jatoh-Nya Sa-Orang President, Penerbitan Utusan Melayu Berhad, chetakan kedua, 1967.

[3] Basyral Hamidy Harahap, Madina Yang Madani, Penyabungan: Pemerintah Daerah Kabupaten Madina, 2004: 20.

[4] Basyral Hamidy Harahap and Hotman M. Siahaan, Orientasi Nilai-Nilai Budaya Batak: Suatu Pendekatan Terhadap Perilaku Batak Toba dan Angkola Mandailing, Jakarta: Sanggar Willem Iskander, 1987: 193.

[5] The idea that the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago and the peninsula are of the Malay stock or race, and its colonial origin is examined in Timothy P. Barnard, Contesting Malayness, Malay Identity Across Boundaries, Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore, 2004.

[6] Adopted by the General Assembly on 18 December 1992 (General Assembly resolution 47/135)

MAINSTREAMING THE MINORITIES: THE CASE OF THE MANDAILINGS IN MALAYSIA AND INDONESIA

By Abdur-Razzaq Lubis

Malaysian Representative, Mandailing All-Clans Assembly (HIKMA)

The issue of our time, the survival of human beings with individuated consciousness and communal ties, is in peril… Freedom, then, is the path to his new life. A freedom which begins with the individual, confirms him in his place with his people [ethnicity] and his language and his culture, yet by that specific location of his being there, grants him a world perspective to recognize his brothers and sisters elsewhere in their ‘different ness’ and their challenge. (The World Crisis)

Who are the Mandailings?

Our homeland is called tano rura Mandailing [the land and water of Mandailing], on the south-western corner of the island of Sumatra. Today it is known as the kabupaten of Mandailing-Natal, or the regency of Madina. The Mandailings are Muslims as well as Christians. For centuries the Mandailings have migrated throughout the peninsula and Indonesian archipelago.

The Mandailing’s most significant contribution to regional peace was to help end the Malaysian-Indonesian Confrontation. The ‘Konfrontasi’ arose as a result of Sukarno’s opposition to the formation of Malaysia, which the Indonesian’s saw as a British-inspired polity. Two Mandailings - Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Adam Malik and General Haris Nasution conspired to broker peace between the two neighbouring countries. At the time of Konfrontasi, Haris was a general in the Indonesian army and his nephew was the chief of staff in the Malaysian navy.[1] General Haris Nasution had flatly refused to go to war with Malaysia as he likened it as fighting his own kinsmen.

Indeed, Adam Malik felt that his main task as Indonesia’s Foreign Minister was to end the Confrontation. He even challenged Sukarno over the matter. He achieved his objective when the two neighbouring countries agreed to end the Confrontation. After the peace treaty was signed in 1966, the first thing Adam Malik did was to make a trip to Malaysia and visited Chemor (his mother’s birth place) in Perak, to reassure his relatives.[2]

In spite of their of their enormous contributions to politics, society, music, literature and the press both in Indonesia and Malaysia, Mandailings continue to be culturally marginalized in Indonesia and Malaysia. Academic works have subsumed them under the categories of the Angkola, Batak and Malay. In Malaysia, racial politics and state-sponsored socio-economic engineering in the name of nation building, backed by the academia, have resulted in the acculturation of the Mandailings into the dominant Malay racial category. In Indonesia, the Mandailings have been lumped into the dominant Batak group since the Dutch colonial era. As a result, the basic human right of the Mandailing to define themselves has been overlooked by most Malaysian and Indonesian intellectuals who have accepted the state’s discourse on ethnicity. Indeed,

In the animal kingdom, the rule is, eat or be eaten, in the human kingdom, define or be defined. (Thomas Szasz)

Are the Mandailings a minority in Malaysia?

What is a minority? Who defines a minority? Who are the beneficiaries of minority rights?

Thus far there are no definite answers. The difficulty in arriving at an acceptable definition of the term ‘minority’ lies in the variety of situations in which minorities exist. Some live together in well-defined areas, separated from the dominant population, while others are scattered throughout the national community. Some minorities has a strong sense of collective identity based on a well-remembered or recorded history; others retain only a fragmented notion of their common heritage. In certain cases, minorities enjoy – or have known – a considerable degree of autonomy. In others, there is no past history of autonomy or self-government. Some minority groups may require greater protection than others, because they are threatened by ethnic or cultural cleansing or facing extermination (genocide).

Despite the difficulty in arriving at a universally acceptable definition, various characteristics of minorities have been identified, which, taken together, cover most minority situations. The most commonly used description of a minority in a given State can be summed up as ‘a non-dominant group of individuals who share certain national, ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics which are different from those of the majority population’. It has been argued that the use of self-definition which has been identified as ‘a will on the part of the members of the groups in question to preserve their own characteristics’ and to be accepted as part of that group by the other members, combined with certain specific objective requirements, could provide a viable option.

As far as statistics go, the Mandailings are in the majority in their homeland, but they are a minority in Indonesia and Malaysia. According to the 2003 census, the population of the regency of Madina stands at 369,691 the majority of which are Mandailing.[3] In 1982, the Mandailing Welfare Association of Malaysia (IMAN) estimated that there were about 30,000 Angkolan and Mandailings in Malaysia.[4] The Angkolan are the neighbours of the Mandailings to the north of the homeland. Many people of Angkolan descent in Malaysia, consider themselves Mandailings. Assuming that the 1982 figures are correct, the author estimates that there are about 50,000 people of Mandailing and Angkolan descent in Malaysia, today.

In Indonesia, the Mandailing ethnic category does not exist as the Indonesian state wants Indonesians to see themselves as bangsa Indonesia. In Malaysia, the DAP’s Malaysian Malaysia, and the government’s bangsa Malaysia is no different. It is expedient for a political party like the DAP or the government to call for a national identity as the DAP dominated by the majority Chinese ethnic group and the government dominated by ethnic Malays, would have their identity secured in the bargain.

Mandailing Dilemma

Suffering from acute identity crises, Mandailings use passing off when convenient. Upwardly mobile ‘passing’ can have its uses; during the period of Indonesian resurgence under Sukarno it was popular to be a Sumatran, but during Confrontation it was safer to be a Malaysian. Since then the Malaysian government has tempted people of Indonesian descent to identify themselves as bumiputra, sons of the soil/land, the natural inheritors of the Malay tradition and rights. In modern Malaysia, passing off as Malays for government contracts, joining the Malay dominated civil service, to enter politics; essentially to climb the social ladder. Mandailing also use regional identities to obscure their descent.

History and nation-building processes has seen to it that the Mandailings people are divided into two ethnic and cultural identities; in Indonesia they are Batak-Mandailing and in Malaysia as Malay-Mandailings. On one hand they are under the hegemony (ketuanan) of the predominantly Batak Christians and on the other, they are under the hegemony of the Malay Muslims. Torn between two religious and ethnic identities, the Mandailings are caught in a dilemma between two equally undesirable alternatives. Both want to appropriate the Mandailing’s differentness.

The pressure to conform to either Batak or Malay identity is both religious and cultural; the difference is that in Indonesia the weight of the state is not behind it. In Malaysia, conformity is compelled by legal means as well as with the might of the state through national policies such as cultural policy and grant concession development. In Indonesia, regional and ethnic identities is experiencing a surge in the euphoria of regional autonomy and devolution of power; in Malaysia the debate that the Mandailings are a sub-group of the Malay stock/race is considered close at the highest level and the thing to do is conform, and not rock the boat.

Although the definition of race remained uncertain, the term itself has stuck in administrative and academic language of today. In vogue is the idea of ‘Melayu inklusif’ (inclusive Malay), based on the colonial perception that the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago and the peninsula are all of the Malay race/stock (rumpun Melayu).[5] The Malay nationalists driven by fears of the ‘yellow peril’ are not letting up in its designs to incorporate the diverse ethnic groups in insular Southeast Asia into the Malay agenda in opposition and to check the so-called Nanyang Agenda of the Overseas Chinese.

Peaceful Coexistence

Because of the legacy of colonial rule in Malaysia, the most important political parties are racial representing the interest of individual ethnic groups. I would describe the brand of majority politics in Malaysia as racial rather than communal. Even though the ethnic interest of the racial trinity of Malays, Chinese and Indians, have been largely attended to, the racial threat remained; Malaysia is also divided along linguistic, religious and social lines. Since independence the principal pre-occupation of the government have been the preservation of the country’s fragile unity and the welding of a truly united nation, of which the survival or eventual demise of the new nation, depends on.

Opposition to the special privileges of one dominant race appeals to the members of minority groups who feel that their own interests are thwarted by the current Sino-Malay-Indian system, which leaves smaller groups in an isolated and exposed position. Communal politics as it serves to benefit a community is in itself not a bad thing altogether, but racial politics by its nature excludes and discriminates. Barisan Nasional (BN) or Barisan Alternatif (BA) pander to, and knowingly or unknowingly serves this brand of politics as their constituents are mainly from the three dominant ethnic groups.

That diversity characterizes the great majority of countries in the world, and that with the end of the cold war and bipolar international order, claims to ethnic, religious, cultural and religious varieties are becoming stronger. The ‘rediscovery’ of ethnicity and cultural identities has created an awareness of the need to cope with the management of ethnic and cultural diversity through policies which promote ethnic and cultural minorities participation in, and having access to the resources of society, while maintaining the unity of the country. The fears that cultural diversity, or multiculturalism, has the potential to foster highly divisive social conflicts owing to the highly contentious thesis by Huntington’s on the clash of civilization in which religion is argued to play a crucial role; it can be argued that the state and social policies can check and intervene and reduce the potential for conflict. Multiculturalism, as a systematic and comprehensive response to cultural, ethnic and religious diversity, with educational, linguistic, economic, social and religious components and specific institutional mechanisms, has been adopted by a few countries, notably Australia (not necessarily a good example), Canada and Sweden.

Special rights for minorities are not privileges but basic civil rights to make it possible for minorities to preserve their identity, characteristics and traditions. Special rights are just as important in achieving equality of treatment as non-discrimination. Only when minorities are able to use their own languages, practise their own religion, culture, etc., benefit directly from state services, as well as participate fully in the political and economic life of the state, can they begin to achieve the status which majorities take for granted. Affirmative action in the treatment of such groups, or individuals belonging to them, is justified if it is exercised to promote effective equality and the welfare of the community as a whole. This form of equitable system may have to be sustained over a prolonged period in order to enable minority groups to benefit from society on an equal footing with the majority. Recognition and entitlements would secure their cultural survival, guarantee peaceful co-existence with fellow humankinds and their well-beings in a world where cultural and human diversity matters. To sum up,

…The promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities contribute to the political and social stability of States in which they live.

(Preamble of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities)[6]

I would add that the promotion and protection of the rights of persons belonging to a minority group contributes to multiculturalism, both to cultural and human diversity, as human diversity is equally at stake today as bio-diversity, threatened by the same forces threatening bio-diversity, that is, globalized homogenized culture, Machiavellian development and malicious capital. We dream of a world where we can afford to sip a cuppa of the famous ‘Mandheling Coffee’ on equal terms.

[1] A.H. Nasution, Memenuhi Panggilan Tugas, Jilid 1: Kenangan Masa Muda, Jakarta: Gunung Aung, MCMLXXXII: 6.

[2] Adam Malik, Mengabdi Republik, Jilid 1 Adam Malik Dari Andalas, Gunung Agung, Jakarta, 1978; Abdul Rahman Rahim, Jatoh-Nya Sa-Orang President, Penerbitan Utusan Melayu Berhad, chetakan kedua, 1967.

[3] Basyral Hamidy Harahap, Madina Yang Madani, Penyabungan: Pemerintah Daerah Kabupaten Madina, 2004: 20.

[4] Basyral Hamidy Harahap and Hotman M. Siahaan, Orientasi Nilai-Nilai Budaya Batak: Suatu Pendekatan Terhadap Perilaku Batak Toba dan Angkola Mandailing, Jakarta: Sanggar Willem Iskander, 1987: 193.

[5] The idea that the peoples of the Indonesian archipelago and the peninsula are of the Malay stock or race, and its colonial origin is examined in Timothy P. Barnard, Contesting Malayness, Malay Identity Across Boundaries, Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore, 2004.

[6] Adopted by the General Assembly on 18 December 1992 (General Assembly resolution 47/135)