Divergent Frontiers: Mandailing Social-Cultural Identity between the Straits of Melaka and the Indian Ocean

Paper to be presented at International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS5)

Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre

2 - 5 August 2007

The Mandailing people and homeland has been, thus far, exclusively and extensively studied and viewed in relation to and compared with the Batak to the north and the Malays to the east of its borders. The fluidity of the social-identity from being a Batak-Mandailing (Batak itself being a contentious ethnic tag) in Sumatra to becoming 'foreign Malays' in British Malaya has been studiously explored albeit the Malaysian experience has not been brought to bear on the Indonesian context.

Due to its position south of the Batak and north of the Minang, nineteenth century ethnologists have been misled and misleading in their readings of Mandailing identity. The Batak have a legend about the origin of the Raja Batak from Padang Mandailing, but conversely, there is no Mandailing story that attributes their origin to the Batak. Another derivative theory about the Mandailing comes from the Minang who consider the Mandailing a ‘people who have lost their mothers’.

Alternatively one can look at Mandailing society and identity as an interior people for west Sumatran port settlements such as Barus, Sibolga, Natal, Pariaman and Padang, ports which were more or less important at various periods in history. They were also connected via Padang Lawas downriver to the east coast of Sumatra and the Straits of Melaka.

The mountain range of Bukit Barisan shaped the trading corridors that extended to all points of the compass, corridors which allowed the Mandailing to flow back-and-forth in a flux of labour migration, cultural exchange and identity transformation. Orientation, language and identity varied according to trading opportunities during different historical time frames. This is one way of understanding why the Mandailing has ‘six languages’, reflecting societal phases, social stratification and occupational specialisations.

One ancient language is the hata parkapur, the language of the camphor-gatherers, indicating a pre-occupation with camphor collection and export through the port of Barus which flourished from 8th to 13th centuries. Barus figures prominently as the conduit for South Indian influence, Hindu and Tamil in particular, spreading into the highlands via Mandailing.

Both Hindu and Buddhist artifacts have been found in and around Panyabungan and Kota Nopan in the heartland of Mandailing itself. The existence of the Buddhist temple complex dating from the 11th to 14th centuries at Padang Lawas bordering the Mandailing region, points to a transit route associated with productive cultivated land, human settlements and religious practices.

Recorded history shows that Mandailings were present all along the west coasts of Sumatra. At the point of Dutch intervention into western Sumatra, both terms, Batak and Mandailing were used to refer to the people of the interior.

Obviously, before colonial intervention and before the opening of the east coast of Sumatra for plantations on the Melaka Straits, the Mandailing were originally orientated towards the island’s west coast facing the Indian Ocean and it appears that they have an early model of maintaining their identity as interior people and subsequently as Muslim but not Malay nor Minang. Taking the queue from Dutch policy that began to focus on east Sumatra in the later part of the 19th century, the Mandailing re-oriented their worldview to the east. By observing them from the western littoral and their relations with the highland civilization, not only can a comparative study be made but a new perspective can be gained with revealing results to illustrate the changing identities in a social, cultural, economic and historical milieu.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Foto Arbain Rambey

API Workshop, Cebu, Philippines

Budayawan Mandailing/A Mandailing Literati

Founder-director, Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Sciences (IFEES)

Horas Mandailing Web Designer

Sponsor, English version of Horas Mandailing

Adat Budaya Mandailing Dalam Tantangan Zaman

Isteri Tercinta/My Beloved Partner

blowing his tulila, a wind instrument, use in courtship music

Dari Hutan Rarangan Ke Taman Nasional

field work in Mandailing/kerja lapangan di Mandailing

Tidak Islamnya Bank Islam: Kritik Atas Perbankan Syariah

Another Malaysia Is Possible

Perajurit, Pejuang dan Pemikir; Warrior, Fighter and Intellectual

Orang Mandailing di Kamp Konsentrasi NAZI

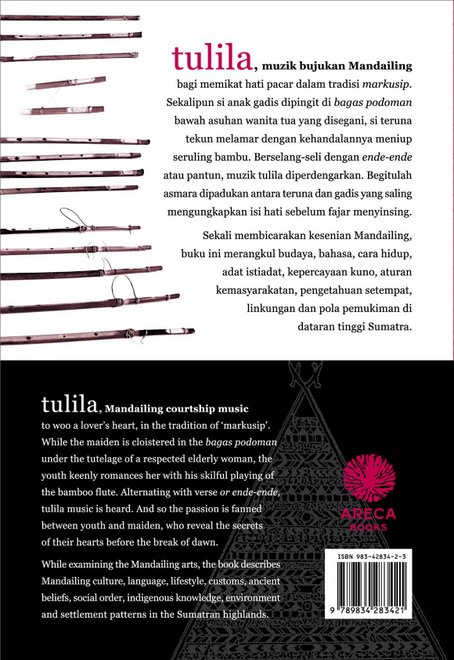

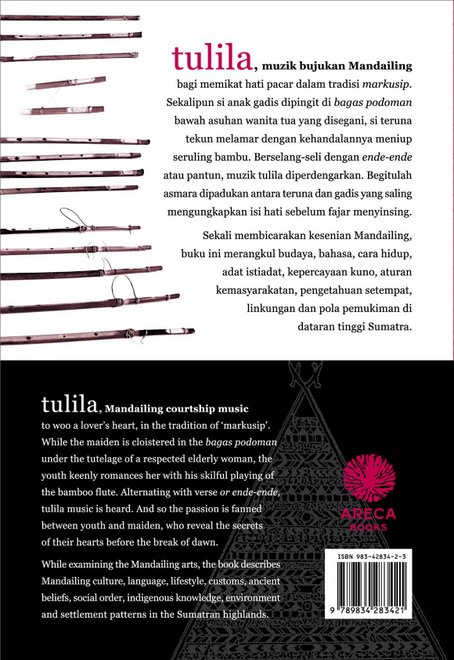

Sampul Belakang/Back Cover

Bumi Bebas champions the cultural survival of the Mandailings as the indigenous people of the Mandailing homeland in Sumatra, and as minorities of the nation states of Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. It promotes the preservation of endangered Mandailing culture, language, identity, environment, traditional governance, music and the arts as an integral part of human diversity. It is run by Abdur-Razzaq Lubis, author of the Horas Mandailing website and director of Areca Books.

New Books! Buku Baru!

Title/Judul : TULILA: MUZIK BUJUKAN MANDAILING

Author/Pengarang : Edi Nasution

First Edition/Cetakan Pertama, June 2007

Soft Cover, 16.5 x 24 cm

Pages/Hlm : 202

Bibliography : pg/hlm 161

Index : pg/hlm 173

ISBN 978-983-42834-4-5

Publisher/Penerbit : Areca Books, Penang, Malaysia.Price/Harga : RM 30 / Rp. 70,000.

Title/Judul: RAJA BILAH AND THE MANDAILINGS IN PERAK, 1875-1911

Authors/ Pengarang: Abdur-Razzaq Lubis & Khoo Salma Nasution

First Edition/Edisi Pertama: 2004

Hard cover, 21 x 30 cm

Pages/Hlm: 278 pages

155 black and white illustrations

ISBN No: 967-9948-31-5

Publisher/Penerbit: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (MBRAS), Kuala Lumpur

Price/Harga: RM 60 / US$20

Order/Pesan : www.arecabooks.com

Author/Pengarang : Edi Nasution

First Edition/Cetakan Pertama, June 2007

Soft Cover, 16.5 x 24 cm

Pages/Hlm : 202

Bibliography : pg/hlm 161

Index : pg/hlm 173

ISBN 978-983-42834-4-5

Publisher/Penerbit : Areca Books, Penang, Malaysia.Price/Harga : RM 30 / Rp. 70,000.

Title/Judul: RAJA BILAH AND THE MANDAILINGS IN PERAK, 1875-1911

Authors/ Pengarang: Abdur-Razzaq Lubis & Khoo Salma Nasution

First Edition/Edisi Pertama: 2004

Hard cover, 21 x 30 cm

Pages/Hlm: 278 pages

155 black and white illustrations

ISBN No: 967-9948-31-5

Publisher/Penerbit: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (MBRAS), Kuala Lumpur

Price/Harga: RM 60 / US$20

Order/Pesan : www.arecabooks.com

MY WEBSITES

Penunggu/Guardian

Foto Arbain Rambey

Abdur-Razzaq Lubis

API Workshop, Cebu, Philippines

About Me

- AR Lubis

- Namora Sende Loebis, author, environmentalist and social activist, is a sixth generation Malaysian Mandailing, grew up in PJ (Petaling Jaya), a suburbd of KL (Kuala Lumpur). His advocacy works include Discredit Interest-Debt! The Instrument of World Enslavement (PAID, 1996); Jerat Utang IMF? Sebuah Pelajaran Berharga Bagi Para Pemimpin Bangsa - Khususnya Indonesia (Mizan, 1999) and Water Watch: A Community Action Guide (APPEN, 1998). He is the author of Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in Perak, 1875-1911 (MBRAS, 2004) Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development (Perak Academy, 2005). His latest work is Perak Postcards 1890s-1940s (Areca Books: 2010) His books are featured on www.arecabooks.com.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(48)

-

▼

June

(36)

- Senjakala Uang Kertas

- Ramadan in Sumatra: The Magical Music in Odd Numbers

- Bahrum Rangkuti

- Mandailing Mart: Trend Social

- Syeikh Juned Tola: Berjasa di Mandailing dan di Se...

- Sinondang Mandailing, Tabloid Bulanan

- Bebas Bunga, Tak Berarti Bebas Riba

- Henry Barlow on Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia'...

- Local history, national interest

- Batara Lubis, Pelukis/Painter

- Census, Map, Museum

- Bangsa Mandailing: Bukan Batak dan Tidak Melayu

- Mengdelling, Mandahiling, Mendeheleng, Mandheling,...

- Jenaka

- Orang Mandailing di Kamp Konsentrasi NAZI

- Mocthar Lubis Receives Ramon Magsaysay Award for J...

- Tidak Islamnya Bank Islam, Kritik Atas Perbankan S...

- The Mandailings in Kinta

- Mainstreaming The Minorities: The Case of the Mand...

- Malaysia Today: A Reflection

- Jejak Mandailing

- J. M. Gullick on Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in...

- Susan Rodgers on Raja Bilah and the Mandailings: 1...

- Book Review: Raja Bilah and the Mandailings in Per...

- Private letters, public concerns

- Kisah Jurnalis Anti Kolonialisme Di Sumatera Timur...

- Contradictio in Terminis: Kritik Atas Perbankan Sy...

- Lawan Dolar dengan Dinar

- Adat Budaya Mandailing Dalam Tantangan Zaman

- Madina Yang Madani

- Abdul Haris NasutionA Political Biographyby C.L.M....

- Sitti Djaoerah: Yang Hilang dan Terlupukan?

- Ulusan Buku: Permukiman Suku Batak Mandailing

- Komentar: Permukiman Suku Batak Mandailing

- Divergent Frontiers: Mandailing Social-Cultural Id...

- Tulila: Muzik Bujukan Mandailing

-

▼

June

(36)

OTHER LINKS

- The World-Wide Web Virtual Library

- ASIAEXPLORERS

- Indonesia journal online

- KITLV Academic journals and articles

- Journal of Islamic Studies

- Martin van Bruinessen

- Project Gutenberg

- Bibliotheque Universitaire Des Langues Et Civilisations

- Kerinci @ Uhangkayo

- Yoo, Rang Talu

- Sekondakhati

- Jalinan Anak Rao dan Persemendaan

- Pertubuhan Banjar Malaysia

- Indonesians in Penang

- Sumatra Heritage Trust

Related Blogs

Z Pangaduan Lubis

Budayawan Mandailing/A Mandailing Literati

Fazlun Khalid

Founder-director, Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Sciences (IFEES)

Mike F. Ionescu

Horas Mandailing Web Designer

Abdul Rahman Iskander Norton

Sponsor, English version of Horas Mandailing

H. Pandapotan Nasution

Adat Budaya Mandailing Dalam Tantangan Zaman

Khoo Salma Nasution

Isteri Tercinta/My Beloved Partner

Edi Nasution

blowing his tulila, a wind instrument, use in courtship music

Drs. Zulkifli B. Lubis

Dari Hutan Rarangan Ke Taman Nasional

Dr. Peter Zabielski

field work in Mandailing/kerja lapangan di Mandailing

Zaim Saidi

Tidak Islamnya Bank Islam: Kritik Atas Perbankan Syariah

From Left, Dato' (Dr.) Anwar Fazal & Dr. M. Nadarajah

Another Malaysia Is Possible

A. Haris Nasution

Perajurit, Pejuang dan Pemikir; Warrior, Fighter and Intellectual

Parlindoengan Loebis

Orang Mandailing di Kamp Konsentrasi NAZI

Tulila: Muzik Bujukan Mandailing

Sampul Belakang/Back Cover