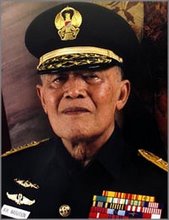

Mochtar Lubis

David Hill

By any measure, Mochtar Lubis was impressive. A mostly self-educated Mandailinger, he was tall, handsome, urbane, and articulate in several languages. Always controversial, Mochtar was one of Indonesia’s most respected journalists and best-known authors for over four decades.

His uncompromising journalistic style, his several substantial periods of political detention, his considerable literary skills and his extensive international connections, all earned him a colourful reputation, at home and abroad. He was an extremely deft ‘cultural broker’, explaining Indonesia to the West, and interpreting Western ideas for his own community.

Born in Padang in 1922, Mochtar was best known as the crusading editor of Indonesia Raya (Glorious Indonesia) daily newspaper, a publication with combative — even ‘muck-racking’ — journalism, dedicated to the exposure of corruption and government malfeasance.

From its establishment in December 1949, Indonesia Raya became embroiled in the divisive politics of the 1950s. In confrontations between the army and the civilian government, Mochtar and Indonesia Raya were often critical of President Sukarno. Critics accused them of serving those military and pro-US interests that were uncomfortable with Sukarno’s non-aligned policies. Mochtar and his staff vehemently denied such claims.

Detentions

Frequent criticisms of Sukarno and his ministers led to Mochtar being detained without trial in 1956. Indonesia Raya closed under pressure two years later. Mochtar spent most of the remainder of Sukarno’s presidency in detention, becoming Indonesia’s best-known political prisoner internationally for most of this period.

Released in 1966, Mochtar revived Indonesia Raya only to have it banned by Suharto after anti-government riots in January 1974. He was imprisoned for yet another year.

In his clashes with authorities, Mochtar dismissed pleas from colleagues to tone down his criticisms in order to be allowed to re-open Indonesia Raya. He argued that the press must be fearless in its criticism of those in power; it must accept banning rather than compromise.

He was accused of being politically naïve, unable to negotiate that fine line trod by savvy Indonesian editors as they struggled to maintain their publications and the livelihoods of their employees despite often-overwhelming constraints on political expression.

But Mochtar’s forthright, combative spirit made him heroic to many. Younger journalists in particular admired the simple clarity of his analysis and his preparedness to speak out.

An international voice

Despite the demise of Indonesia Raya, he remained an editor at heart, active internationally in the International Press Institute and the Press Foundation of Asia. For 36 years he edited Indonesia’s leading monthly literary magazine, Horison, founded in 1966 on the initiative of young anti-Sukarnoist activists.

As a measure of his international standing, he was appointed to the UNESCO Commission for the Study of Communication Problems (1977-9). This made Mochtar, at that stage, one of only four Indonesians to have been appointed to such UN commissions.

At home, he maintained his feisty opposition to the prevailing political authorities through support for various non-government organisations, such as the Jakarta Legal Aid Institute, and the environment movement. Yet he also became a life member of the establishment’s most prestigious and exclusive intellectual and cultural body, the Jakarta Academy.

During his periods of detention Mochtar still wrote energetically, producing a string of novels, short stories and children’s tales as well as some poems, diary accounts and biographical sketches, garnering a string of awards.

Literary achievements

In 1958, while under house arrest, he was the first Indonesian (and remains one of only three) to be given the prestigious Magsaysay Award for Journalism and Literature. His strong anti-leftist views led him to return the Magsaysay Award in protest in 1996 when leftist author Pramoedya Ananta Toer received the honour.

Most highly regarded of his literary works was his novel Jalan Tak Ada Ujung (Road with No End), which explored fear and courage during the Indonesian revolution, and for which he won a national Literary Award in 1952.

But what sealed his reputation internationally was his pillorying of the self-interested politics of Sukarno’s Indonesia in Senja di Jakarta (Twilight in Jakarta). This was the first Indonesian novel ever translated into English.

Most touching perhaps remains his 1959 short story, Kuli Kontrak (Contract Coolies). This is an account of a childhood experience secretly witnessing his father, a Dutch-appointed administrator, overseeing the whipping of indentured labourers in the local prison.

Tragically Alzheimer’s disease stole Mochtar’s memory during his final years. Yet when he passed away in Jakarta on 2 July 2004, aged 82, his moral courage, revered journalistic principles and literary achievements left an enduring legacy.

David Hill (dthill@murdoch.edu.au) is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Murdoch University, and a biographer of Mochtar Lubis.

http://www.insideindonesia.org/edit83/p23_hill.html